By Brian Owens

Reporter, The Courier

There is no evidence that the apparent cluster of undiagnosed neurological illnesses in New Brunswick is caused by environmental contaminants, according to the results of an investigation by the province’s Chief Medical Officer of Health.

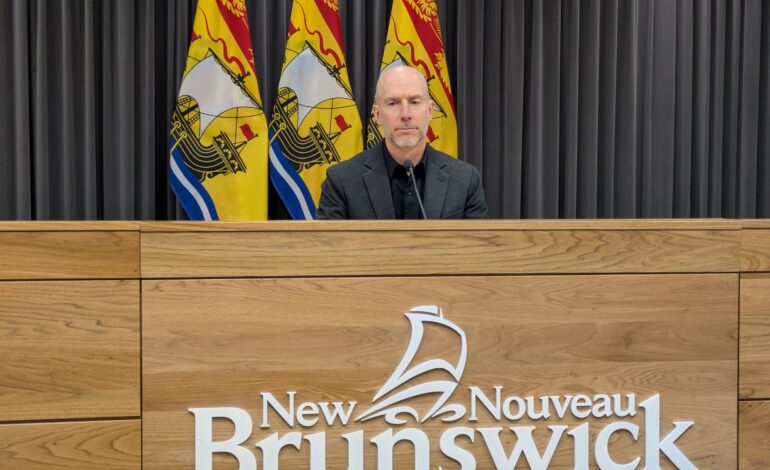

“Our findings do not suggest widespread exposure to herbicides or metals that would be a contributing factor to these illnesses,” Dr. Yves Léger said at a press conference in Fredericton on 23 January.

The existence of a potential “mystery brain disease” in the province was first suggested in 2019 when a neurologist in Moncton identified several patients with unexplained neurodegenerative symptoms. Since then almost 400 possible cases have been identified.

But an investigation by Public Health New Brunswick, published in 2022, concluded that there was “no evidence of a cluster of a neurological syndrome of unknown cause”, a conclusion supported by an independent study published in May last year.

The latest study began in 2023, when Dr. Alier Marrero, the neurologist who first identified the potential new disease, raised concerns about potential new patients who also had elevated levels of substances such as herbicides or metals in their bodies.

Léger and his team reviewed records for 222 patients, looking at two herbicides – glyphosate and glufosinate – and nine metals including aluminum, lead, mercury, and arsenic. Three other metals – cobalt, nickel and zinc – had two few samples to include in the analysis. They examined whether the levels detected were above the laboratory reference levels, how those levels compared to the population at large, and whether there was any published guidance that indicated the levels detected might have any health effects.

The analysis of the herbicides found that 95 per cent% of the results were within the normal expected range of lab reference levels, and were similar to the levels seen in Atlantic Canadians at large.

“They were unlikely to be levels that would be of concern for these patients,” said Léger.

For the metals, some patients had levels higher than expected, but most were not. Most were also the same as those in the wider population, though some were slightly elevated. They were only able to find current health guidance for aluminum, with only a few patients over that value.

Léger said the investigation faced several major challenges that made it difficult to answer some questions. Not all of the labs that performed the testing provided information on how they set their reference levels, and in some cases information on the wider Atlantic Canadian population was not available for comparison. In addition, not all of the patient tests were done using the correct specimen, for example blood or urine, for the substance being investigated. And very few of those who tested high were retested to confirm the result, which is best practice in these cases. Of those that were, the vast majority returned normal results on the follow-up test.

Despite these limitations, Léger said he was confident in the conclusion that there is no widespread environmental exposure that is contributing to these patients’ illnesses. The study underwent two rounds of scientific review by experts at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

Though it was not the main goal, the study also added to the evidence that there is no new, unknown disease in play. The team examined autopsies for nine patients who had since died, and in all cases determined they had been suffering from well-known conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Almost 60 per cent% of the patients had also been examined by another neurologist and none had raised concerns with Léger’s office.

Dr. Anthony Lang, a neurologist at the Kembril Brain Institute in Toronto who led the independent study last year, said these results confirm his earlier belief that it was unlikely there was any consistent environmental factor causing the diverse neurological diseases his team diagnosed in the patients they studied.

“This proves the whole concept of a neurological condition of unknown cause was a house of cards,” he said. “It was based on one individual’s belief, without sufficient clinical or laboratory evidence.”

Marrero did not respond to a request for comment before deadline.

The report includes three recommendations. First, tests for environmental exposures should be repeated at least once, and preferably multiple times, using the correct type of sample. Second, these patients should receive an independent second assessment, to help them get a diagnosis and the follow-up care they need. The regional health authorities will take the lead on arranging this, Léger said, and will reach out to patients directly.

“You’ve been told you have an undiagnosed illness, but you likely have one that can be diagnosed,” he said.

Third, Léger wants any future potential diagnosis of an unknown neurological illness to be reviewed and agreed upon by two specialists before it is reported to the government.

The process is not yet finished, however. The Government of New Brunswick has also asked PHAC to conduct a second review of all the data from this investigation. There is no timeline yet for that review.

Lang said he believes there should be an investigation into the costs of this whole process to New Brunswick’s health system – both the cost of unnecessary testing and the various government reviews.

“That might not have been needed if the patients had first received an independent second opinion,” he said.

Lang also said Marrero should be reported to the New Brunswick College of Physicians and Surgeons for possible investigation. Léger said questions about Marrero’s competence will be left to his employer and the college.