By John Chilibeck, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

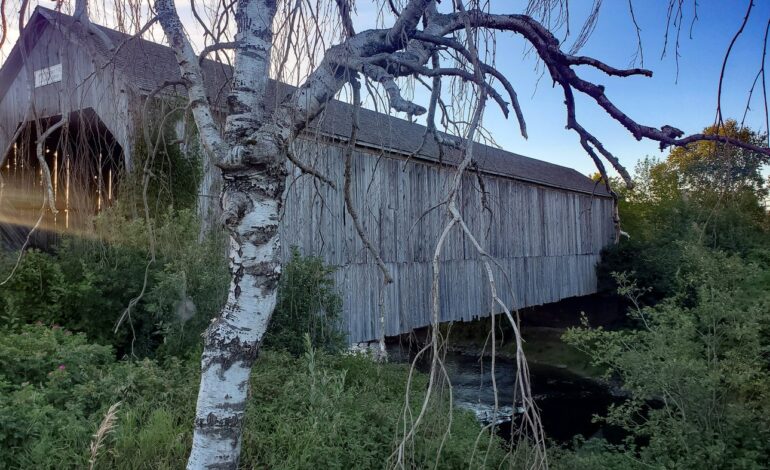

For over 50 years, Bev Mitchell has lived near the quaint Poirier covered bridge, about a 25-minute drive north of Moncton.

He still passes it daily on his walks with his trusty shepherd by his side, even if the sound of machinery buzzing on it is distressing.

Reminiscing, he chuckles at the thought of the wedding party that had to send for a painter to cover up some lewd graffiti on the bridge before the photographs were taken of the bride and groom at the cherished pastoral scene.

Mitchell also fondly recalls the children who would play nearby and swim in the cool waters of the Cocagne River below.

But now, like two other historic covered bridges that met their demise in the province this year, the Poirier Office Road Covered Bridge is coming down, the victim of neglect and disrepair.

Despite covered bridges promoted on tourism brochures and as familiar to New Brunswickers as lighthouses, sugar maple taps and lobster traps, the Holt Liberal government has no special plan for saving them.

Mitchell thinks that’s a mistake.

“I come down here probably two or three times a day. And believe me, I’m going to miss it,” he said recently as workers from the Department of Transportation disassembled the wooden span built in 1942, soon to be replaced by a steel modular bridge. “The guys working on it said that was one of the better ones they had to dismantle.”

Preservationists are lamenting that New Brunswick lost three covered bridges this year, the greatest number that has perished in a single year since 1989, leaving the province with only 56. In their heyday in the 1940s, the province had 340 covered bridges, one of the greatest collections in Canada.

The William Mitton Covered Bridge in busy Riverview was demolished in late February, and the Shepody River No. 3 Covered Bridge, also called the Germantown Lake bridge, in Albert County, visible from Route 114, a major tourism corridor, was taken down in April.

Kelly Cain, the deputy minister of transportation and infrastructure, or DTI, told a committee of politicians on Oct. 3 that covered bridges are triaged just like any other spans in the provincial network.

Overall, New Brunswick has more bridges, roads and culverts than it can pay for upkeep and repair. The province prioritizes infrastructure that has more traffic, often leaving covered bridges in less busy rural areas behind.

“The covered bridges fail, and you can’t use them for transportation, school buses can’t cross, garbage trucks can’t, nothing,” she said. “Everybody wants you to keep the covered bridge and fix the covered bridge for pedestrians and ATVs and snowmobiles, which isn’t really, quite frankly, necessarily the number one mandate of DTI. Those are ‘nice to haves.’

“So, you can invest all your money, because you only have so much, or actually spend it on transportation connectivity.”

Cain, who used to be the deputy minister of tourism, said covered bridges were “beautiful” and “iconic,” but her department did not have enough money to give them special attention. Her department’s mandate, she reminded the politicians on the public accounts committee, is to get traffic to where it needs to go as efficiently as possible.

“We have another one in St. Martins, everyone knows that’s the kissing bridge,” Cain said. “But to preserve and protect these assets simply for pedestrian recreational leisure use isn’t necessarily the mandate of our department in the throes of all the other things that we have to deal with.”

Bill Caswell has heard that argument before. The long-serving president of the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges in the United States says officials often forget that the historic spans are appealing to tourists who have money to spend.

A native of Rhode Island, Caswell had never seen a covered bridge until he graduated from college and moved in 1984 to take up a job at the New Hampshire Department of Transportation.

A supervisor gave him a pamphlet and told him if he wanted to get to know the state, start with the covered bridges.

It wasn’t long before Caswell began driving his family to out-of-the-way spots, eager to see something beautiful and different.

“Sunday afternoon drives became weekend long trips, became weeklong vacations,” he said, recalling he’d often pack up the camper with his kids. “From New Hampshire, to Vermont, to Quebec, to New Brunswick.”

Those trips have special memories, such as his middle daughter out of five children celebrating her 19th birthday in New Brunswick on a covered bridge and lighthouse tour, enjoying her first legal alcoholic drink.

Caswell has seen all 56 remaining covered bridges in New Brunswick and some that have since been destroyed. Most recently, he came to see the Mitton covered bridge last year before it was gone.

“It gets you off the road, going to see covered bridges. It gets you to places you normally wouldn’t see just driving the highways. And it wasn’t just the bridges – it was being able to explore these other communities and areas you wouldn’t normally visit,” he said.

“There’s a benefit to promoting that. You draw the tourists in, you bring them in to see the bridges, and they spend money at the restaurants and the hotels and the shops. There’s an economic benefit to the community when you promote covered bridges.”

Caswell recommended New Brunswick politicians and policymakers look at Vermont’s dedication to preserving its covered bridges, which began in earnest more than two decades ago. He said some states, counties and local towns in the United States have had such success celebrating their covered bridges that they are now erecting new ones.

The United States has about 850 covered bridges, most of them in the northeast of the country, but only 600 are considered historic. Only the state of Pennsylvania, with more than 200 covered bridges, and Quebec, with 88, have bigger collections than New Brunswick’s.

Patrick Toth, president of the Covered Bridges Conservation Association of New Brunswick, doesn’t want his province to lose any more of the iconic spans.

He’s seen several success stories when communities rallied to save their bridges. A resident of Moores Mills, in the southwestern corner of the province, he remembers in 2013 when Trout Creek No. 5 Covered Bridge about five kilometres from his house was hit by a car. The province planned to replace it with a steel bridge, creating a public outcry. Following a public meeting, Toth said, the local MLA Robert Tinker got involved, and the bridge was eventually repaired, strengthened, and re-opened.

A similar rally was held to save the Vaughan Creek covered bridge in St. Martins. Because of the high volume of traffic going to the Fundy Trail Parkway, the province ultimately decided to build a new wooden span in 2022, the first double-barreled covered bridge in Canada, itself a tourism draw.

“Politics got involved, that’s why it was saved,” Toth said. “It’s the same in Hartland. They have the longest covered bridge in the world, and it gets a lot of attention. A lot of the other bridges, they’re dear to the locals, ‘I learned to fish there with my grandfather, and I learned to swim there underneath,’ and there are all kinds of nostalgic stories, adding an intrinsic value to the bridge other than a transportation network across the stream. But they’re not seen in the same light by DTI.”

He was saddened to see the Poirier bridge dismantled. Last month, he walked across it, half way through the demolition.

“I’ve seen bridges in a lot worse condition that were saved.”

Having met with DTI officials in the past, Toth believes the only way to save New Brunswick’s covered bridges is for local communities to rally and fight for their preservation.

“Public awareness is vital. People say, ‘oh, I thought covered bridges were protected.’ Well, they’re not. Unfortunately, DTI runs hot and cold on this issue depending on who’s in office.

“It’s up to the public to push back and save our covered bridges.”

– with files from Sarah Seeley